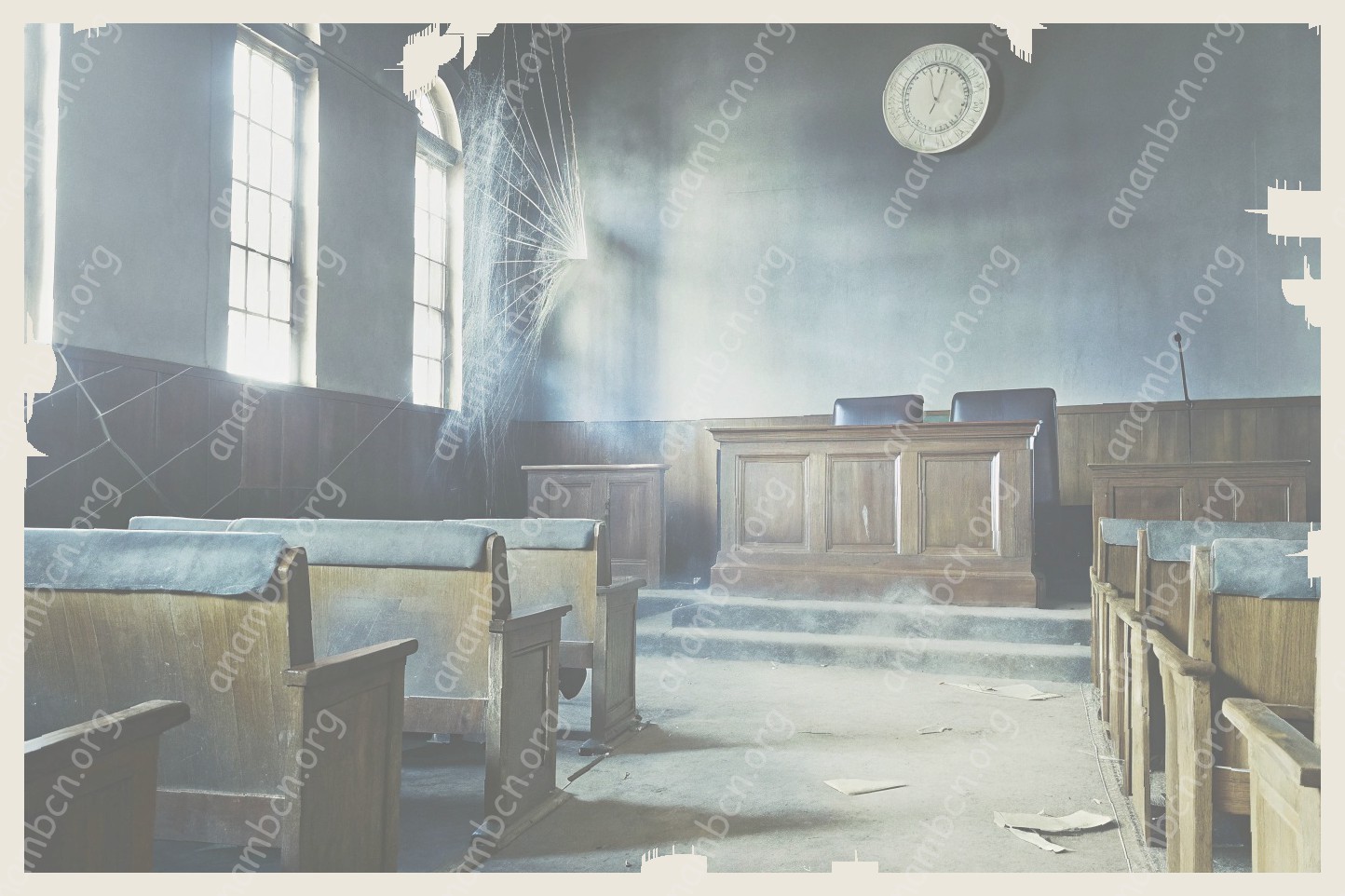

The Mass Closing of Trial Courts

Part of the challenges with understanding mass trial court closings is that it can be hard to figure out when and how we got here. We are not necessarily the most historically inclined creatures, many of us, and so looking back a few decades can be a challenge.

The reasons for mass trial court closings have varied. For example, budgetary shortfalls, created by the 2008 recession, were justified and necessary reasons for cutting services to trial courts. The economy in 2008 was in absolute free-fall. The States were reeling from a mess largely created by abuses of the mortgage lending system, and the federal government was bailing out the banks. The State rental income fund that operated Illinois’ rent from the State Building, 160 N. LaSalle St., was lowered by $180 million in one year. In 2009, the State rent generated $91 million in income; by 2012, the State rent generated only $26.8 million in income. In the 2010 Budget it was only funded at 13.2%. This was not enough, and the courthouse administrators decided to save money. They just cut everything in half. It made absolutely no sense and resulted in chaos. In 2009 , because of staffing shortages, there were 250,000 fewer criminal cases resolved, 212,000 fewer divorce cases in counties that represent 90% of Illinoisans. The number of guardianships decreased by 40% or 82,000 cases. Unrepresented cases went from 484,000 in 2008 to 522,000 in 2009, while the real number of bankruptcies rose 66% to 51,000 cases. The State spent 43,000 fewer hours assisting self-represented litigants. The fallout from this loss of access to justice can be seen today, in everything from the pro se divorce forms pandemic, to the recent push to "ban bench trials". Moreover, since then, trial courts have struggled to adapt to the ever increasing monthly rent on 160 N. LaSalle St. For example, in 1994 the monthly rent was $526,000 per month. By 2013, the monthly rent on the State Building reached $1,163,000 per month. At least once every three years the rent would increase dramatically. That was $13.95 per square foot in 1994, while in 2017 the monthly rent increased to $24.11 per square foot. This directly affects courthouse delays.

Social and Legal Consequences

The legal implications and social consequences of mass trial court closings must be taken into account for any comprehensive understanding of the issue. Initial backlog and delay consequence may lead to mounting systemic problems that stack up on top of an already reorganized court system. A reduced number of courtrooms and reduced funding can lead to a disparity in the justice that plaintiffs and defendants receive. When some courts are delayed for trial, those who can afford the time or money for alternative resolutions may escape delayed justice while others are denied the option. This problem is further exacerbated when court closures result in reduction of juror selection processes.

A lack of financial resources hampers the state system and local system in how quickly they can eliminate the backlog, and how they can approach addressing crisis with a one-size-fits-all mentality. Many argue that since there is sufficient cause to believe that the courts will not be reopen soon, that partial or full restitution credit programs (Texas, for example) should be introduced to ease the burden of overcapacity in an already strained system. However, such a one-size-fits-all approach does not taken into account the additional administrative costs that can arise when implementing a new program. For example, additional staff, ongoing training and continual implementation monitoring are all costly and are all subject to available state funds.

Jurisdictions who choose to adopt a partial credit or full credit process, or implement a surveillance system to track and monitor their engine of justice face an even greater challenge in the lack of available state funding. Likely scenarios include an across the board reduction in administrative personnel and/or clerk positions in an effort to save finances. The long term result of this may be that those who are chosen to handle these new docket schedules without proper training may lack the expertise to do so. In an effort to save money, the state may be forced to rely on understaffed administrative personnel to oversee a smaller docket size. This can overburden already strained administrative members and lead to mistakes and the failure of accurate caseload accounting. This could snowball from one mistake to another and create a chain that can have negative impacts on trial outcome.

The social implications are exact opposites of the legal implications and create an unequal dichotomy. Under the current financial and political climate, measures to prevent mass court closures do not appear on the horizon. As court closures spread across the country hundreds of thousands of jurors, trial participants and observers are being affected by the ensuing backlog. The longer the backlog persists, the more jury pools shrink as citizens refuse to participate in a system that seems hopelessly broken. Regardless of the reasons, larger juror pool sizes make it more likely that jurors will have other obligations or time demands that lead them to either serve on a given case or to defer or cancel that service.

Case Study: Recent Scenarios

In 2008, the Commonwealth of Kentucky closed fifty-one of its trial courts as a result of shrinking revenues from the state’s declining economy and reduction of funds from the federal government. Although state government paved some new court structures, these facilities were located in larger cities that would require victims and witnesses to travel far distances which would interfere with their ability to attend trial. Some victims and witnesses had to drive up to three hundred miles to attend a trial in a neighboring county. As a result of this effort, the number of trial court cases tried on the same day dropped from an average of nine a day before closings to one per day in most of the closed courts. In the remaining jurisdictions where courts actually remained open, there was a backlog of cases. The American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky filed a class action lawsuit in the Kentucky state circuit court against the Chief Justice, the former Court Clerk, and the then-acting Administrative Office of the Courts claiming that under the Kentucky Constitution, the courts could not be closed due to state budget problems nor may the legislature reduce court budget expenditures without also reducing all government expenditures equally. In December 2008, the Kentucky Circuit Court ruled that the plaintiffs had "shown an irreparable injury" and ordered that the courts must remain open with a single month-long exception of February. The disruptions to trial schedules resulted from this "interruption of court business," therefore, all cases scheduled to be tried while the courts were open in January were continued to February. Cases set to be tried in February were continued to March. In April, the Kentucky Supreme Court overturned the circuit judge’s ruling in favor of the Kentucky state and ruled that the judicial branch of government could close a court facility when stated appropriations for the courts are less than the amounts necessary to fully fund the court system in Kentucky. In light of the budget shortfall, the Judicial Branch, without legislative approval, closed fifty-one out of the total 120 Kentuckian courthouses. The Kentucky Supreme Court noted that "a decision to deny a quorum of trial judges to allow trials to proceed in a particular locality [may] rise to the level of interference with a party’s right to a trial," however, "that right is not inviolate." So while, the Kentucky Supreme Court recognized a party’s constitutional right to a fair trial, the court did not extend this right to mandate that the closure of courts was impermissible despite this right. The court concluded that the closings were permissible.

Other Options and Innovations

In lieu of closing a mass trial court, jurisdictions across the country have explored alternative solutions as a means to helping the court navigate budget constraints. For example, in hopes of avoiding court closures, both pre- and post-expiration of a state tax surcharge levied by Congress, Missouri adopted some innovative courtroom management practices. In 2007, after the expiration of the Federal Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, the Missouri legislature enacted a one-time, $50 surcharge on all circuit civil filings in an effort to postpone court closures until December 31, 2008. While many state tax surcharges are levied on individuals or corporations based on their taxable income, the Missouri surcharge is levied only on civil court filings. The courts reported an annual $6 million increase in civil filing revenue from the surcharge. After receiving taxpayer approval, the surcharge was repurposed to fund a state-of-the-art electronic filing system in 2010.

The District of Columbia’s Administrative Office of the Courts restructured its business operations to avoid court closures during the 2002 fiscal year. The court initiated a "permanent measures" project that included: (1) establishing an Information Technology Department Division to ensure salaries for the IT staff, (2) hiring new clerical staff and providing training to current clerical staff, (3) reducing overtime expenses by 50 percent, (4) retraining staff to perform various duties in order to minimize layoffs, and (5) introducing a tax levy program that generates revenue by levying taxes on city residents for court support. According to the District of Columbia Courts, in 2006, the tax levy program raised $14.6 million in revenues , which went toward the District of Columbia Court’s $115 million budget.

The chief judge of the New York State Court of Appeals announced in 2011 that in response to the economic crisis, the court will not hold argument for assigned cases during the month of July 2011. The court’s administrative director explained that to avoid court closures and layoffs of support staff, the court plans to adjust hearing dates throughout the calendar year.

As cash-strapped federal and state governments struggle to make ends meet, their judiciary system is being forced to do the same. The National Center for State Courts has developed "The Justice Index," which is a resource that assists state courts in finding new and innovative ways to provide access to justice. Featured at the Justice Index web portal are advancements in the areas of case processing, case technology, court finances, and court user services. State courts are using technology to gain efficiencies so as to provide access to justice to the public. The Justice Index reports that Kentucky courts are using block scheduling innovations to increase the efficiency in the processing of civil, criminal, and juvenile cases. Block scheduling allows judges to set aside an entire day for family, criminal, juvenile, or civil matters, which helps to reduce backlogs in the system while improving the public’s overall perceptions of their judiciary system. It makes the judiciary system more accessible to the public in that court appearances are scheduled in a manner that allows the judge to give his or her full attention to each case on his or her docket. In Clay County, Texas, electronic bench warrants for arrest are issued through the use of technology at the police station, resulting in a smoother process and quicker arrest of the accused.

Possible Directions and Recommendations

The future impact of the mass trial court closings and the resulting empty buildings, fewer staff and shrinking budgets is difficult to predict, in part because at this point in the year decisions at the District Court level for the upcoming year are being made and at both District and State Supreme Court levels next year’s budget is being created. In the short term, as a practical matter staff will be eliminated, and in the case of under, or unused, space, buildings will be moth-balled with a likely result that those buildings will not be re-opened.

Some recommendations are offered:

Repopulate the courthouse – open satellite courthouses in rented or under-used buildings; Convert under-used spaces in existing court buildings to administrative use or office or housing for Departments of Social Services or other state agencies; Invite community-based organizations to use space for mediation, early resolution of cases, child visitation, etc. to be more accessible; Shift more work to the out of court process, writing contracts with community based organizations to manage cases or resolve conflicts early; Move to more self help, web-based and in-lobby aid; Embed the sheriff in the court; Foster more collaboration between stakeholders, with a focus on resource sharing and reallocation; Focus on early resolution of cases; Streamline and standardize court calendars; Explore consolidation of resources for small caseload courts, focusing on specialization; Explore regionalization of courts; Explore outsourcing for services; Outsource more judicial functions; Explore alternative judicial models; Develop alternative funding sources; Invest more in a modern case management system to improve data collection, and to move to based risk based treatment plans (e.g . , use regression methods to determine the risk of recidivism or re-offending); Expand eligibility criteria for judgment programs or sentencing deferments of some sort; Decentralize earning capacity analysis, perhaps using a low income scale instead; Move more probation officers and court staff to the community; More use of citation-only systems, peer courts, or community based diversion models for low-income defendants; Increase jail alternatives; Focus on mental health; and Develop better data analysis methods to estimate state needs and resources.

Among the long term changes that could happen which would revolutionize the system include the following:

Separation of lower value infrastructure from higher value infrastructure and merging amounts spent for low and mid-value infrastructure; Separation of pre-trial and post-trial court functions; Separation of primary registry of actions/sealed files from lower-value function; and Transfer of lower-value functions to other departments (e.g. Unemployment Insurance Appeals, the Campus Human Service Center).

Lastly, there is the question of how these trends impact stakeholders and how stakeholders can impact the trends. As the question is posed by one court stakeholder organization, Reforming the Courts In New York State suggest that

State policymakers are readily tempted to reduce budgets in a one-size-fits-all way. But when it comes to court services and facilities, such analogies do not work. Some parts of the Courts are in fact profit centers and should be financially healthy. Other parts of the Courts are in fact badly eroded and patently unhealthy. The relative degree of profitability and sickness varies widely from court to court around the state. The Courts are therefore well-advised to work with policymakers to root out waste and inefficiency and to reallocate resources as needed. But make no mistake: too many courts are already operating in a state of siege. And if various proposals from the Legislature and the Executive come to pass as they have been articulated, our Courts will simply collapse.